The Beautiful Order of The Witness

I write scripts with a college friend of mine. We make a strong partnership because we both prioritize the same elements of movies and screenplays, but for as many things as we have in common, we disagree all the time on just about everything. Most of my favorite movies come from the '70s golden age. A Clockwork Orange and Network. That kind of thing. I'm generalizing here, but my friend loves '80s blockbusters. Back to the Future and many an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie.

Though we disagree on movies quite a bit, we disagree even more on music. There's plenty of overlap. After all, we did write a musical together. But on a basic genre level, I’m a hip hop/soul/jazz person and he likes electronic and dance. More importantly, however, we share differing philosophies over what we find meaningful in our music.

Some sounds mean something to me and some don’t because of whatever arbitrary bullshit going on in my brain, but generally speaking, I find beauty in the expression. An artist creates a piece of work to articulate a feeling or thought, and I seek to understand whatever that something may be and respond to it. Because of this, I don’t really care if my music is smooth, chaotic, abstract , or forthright. I just want to feel.

My friend responds to different kinds of sounds, from synths to tame guitars to coke-y club bangers. (Note: My friend does not partake of the cocaine.) While there’s certainly eclecticism to be found in his library, all the songs he plays for me follow a general blueprint. There's a very simple pattern, then a layer gets added, then another one, and the song builds on it until there's a climax. Most of the time, the song slowly goes back to the base pattern, and the song ends without really surprising you. (I realize I'm describing most songs, but... just listen to the embeds.) As a result, because I’m an asshole, I like to give him a hard time. I tell him that his music sounds “like math” and “like it was constructed by robots.” “Clockwork” is the term he used once.

Everyone is, of course, entitled to their own tastes. We have little control over the rules that govern what we respond to and what we don’t. Yet, I struggled to understand his perspective. I found the music he played for me frigid and lifeless, and I couldn’t comprehend what anyone could see in it.

Then one day, I started playing The Witness, a beautiful puzzle game created by Jonathan Blow and his team at Thekla Inc. (The following section was written for people who don’t play games or haven’t gotten around to playing The Witness. Sorry to bore those who have and SPOILERS for those who haven’t. Feel free to skip ahead and I’ll add a line to tell you when to start again.)

JUST TO REITERATE, THERE ARE SPOILERS AHEAD, INCLUDING PUZZLE SOLUTIONS!

The Witness starts you out in a cold circular hallway. You don’t know who, or what, you are.

You approach the door. It has a panel with a simple shape: A circle that leads to a rounded end.

The game tells you to press a button on your controller or keyboard. A border surrounds the screen and a little dot appears. You soon learn that you position your dot in the circle and draw a line to the rounded end.

The door opens. You’ve solved your first puzzle. You approach another door with a similar panel, only this one has an angle. Easy enough.

You open the door and you emerge out onto... a gorgeous courtyard. You can see your shadow. You're humanoid in shape, but there's no way of knowing for sure.

You walk around and see that you’re trapped in the area by a gate. You notice that the gate has a panel with metal plates blocking you from engaging with it, but you also notice that there are a few thick wires emerging from the panel. You follow the wires and find more puzzle panels.

The panels in this section contain simple mazes. Once you solve a puzzle, a wire lights up and a metal plate on the gate panel opens. Once you light up all the wires, you can interact with the panel and open the gate. You are now free to explore your surroundings.

You soon realize that you’re on an uninhabited island. We see evidence that there was civilization once. Buildings ranging in different eras of technology scatter the island, but you can’t really tell if everyone died out or left. Maybe this is all some big construct built explicitly for you, but again, you don’t have any way of knowing for sure. (There are hints in the endgame, but I don’t want to spoil that much.)

As you roam around the island, you encounter different environments and settings, all with a different set of puzzles that teach you new concepts and rules. The order in which you approach each area depends on you, but there are some sections you simply cannot complete unless you’ve mastered a rule taught to you in another zone of the island.

If you follow the path out of the courtyard, you’ll run into a set of introductory puzzles that teach you basic rules that’ll apply to every section you encounter. For example, this set teaches you a rule that if you see a puzzle with black and whites squares, you must separate the white squares from the black ones and vice versa. (Sorry about the sunlight on the panels.)

The first full section I came across was a building that seems to hold some kind of glass workshop.

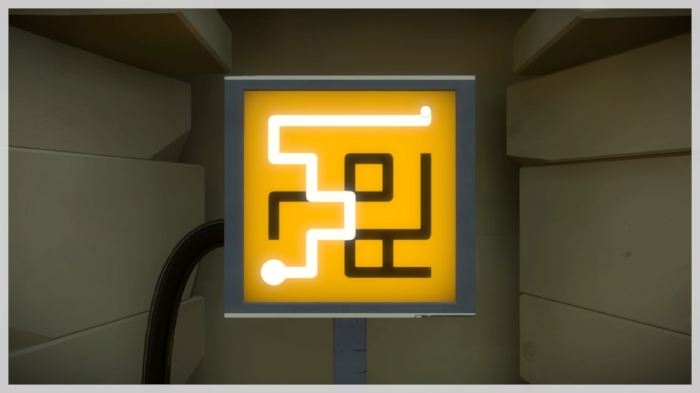

Once inside, I found this set of puzzles:

I soon learned that the gimmick here was that I was controlling two lines at once, and the solution would create a symmetrical pair of lines. I solved the puzzles as such:

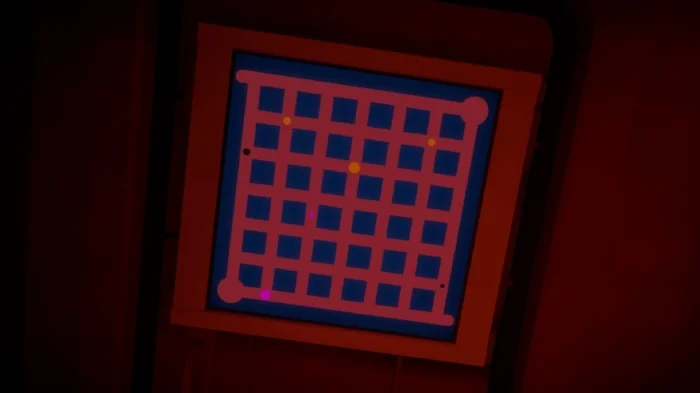

I finished the rest of the puzzles and followed the glowing wire to a small island nearby. The puzzles on this island continue to play with the idea of symmetry. Some puzzles require you to cover all of the dots:

Some require you to consider the shape of the surrounding rock formations and trees.

The next set of puzzles changed the color of one of the two lines you control, as well as the color of the dots. The blue line has to cover the blue dots and the yellow line had to get the yellow dots.

You get a few more sets of puzzles, all of which increase in complexity. One you solve all of the them, you activate a machine that beams a laser…

…towards the mountain in the distance.

While each zone incorporates the panels, they contain different kinds of puzzles. The panels in the early parts of the desert section become solvable once you consider the sunlight.

To solve the early puzzles in the monastery, you have to stand behind the building's metal works.

Other sections incorporate sound while others teach you symbols that dictate rules you have to figure out on your own with trial and error. Each mechanic builds on top of the next and the puzzles become more and more difficult. Eventually, you’re going to encounter puzzles like this piece of shit.

Or this... fucking... goddamn... fuck.

This is one of the hardest puzzles in the game, and it may be my biggest gaming accomplishment ever that I solved it without internet assistance. I understood the basic logic, but I'll admit that a ton of brute force and coincidence were involved. It took me a VERY long time to solve. I'm talking days, and because I'm a spiteful asshole, I won't post the solution to this one. (To non-gaming readers, you don't have enough information to solve it.) I can't prove to you that I solved it without the internet, but to show you that I did, in fact, solve it on some level, here's a picture of what's behind the door:

If you want to know that badly, reach out to me on Twitter or something. Or just Google it.

You complete enough zones, you activate enough lasers, and eventually you open the door at the top of the mountain and discover the secrets inside and complete the game. (Guess what? There's more puzzles)

However, it's possible to play through the game without noticing a certain element. As I left the opening courtyard, I stumbled upon this:

I wondered out loud, “Can I?”

Yes. I could. There are puzzles hidden throughout the environment and they are all…

…over…

…the…

…fucking…

…island.

Yes, I know how to get rid of the gray part.

After making this realization, I basically decided that everything I saw was a puzzle, and I would stop and inspect anything that even remotely looked like a circle.

It was also around this point that I fell deeply in love with this game. I loved playing it. I loved figuring out the puzzles. I loved the feeling of smugness that filled my heart because I wasn’t cheating and looking up any of the answers online. Most of all, I loved looking at it, not just for the aesthetics which are breathtaking in their own right, but because everything I saw could potentially be a new puzzle. It was up for me to find out.

One day, I was walking down the street. There was a construction site on the other side of the road, and the traffic light was turning yellow at the intersection. I looked up to discover that from my current perspective, it looked like the yellow light was blending into a line formed by the yellow crane of a construction truck. Unfortunately, I don’t have a picture to share with you, but it looked exactly like a puzzle from The Witness. In my mind, I set my dot at the traffic light and followed the line down to some point near the tires. “Holy shit,” I thought, “There are circles everywhere. There are Witness puzzles… everywhere.”

Just like in the game, every circle I saw in the real world could potentially be a puzzle. My plates. My doorknobs. The little metallic trashcan I keep next to my desk. The tops of the vast quantity of empty Diet Dr. Pepper cans that litter all my tables. Rarely would the colors match up and there weren’t as many rounded ends, but there was always a circle, always a line, and I could always follow it to a certain point.

I found myself constantly searching around my environment to try to spot a potential Witness puzzle. Whether I was stuck in traffic or distracting myself from writing or trying to annoy another friend of mine who had watched me play some of the game by pointing out all the circles in her apartment. It was a fun way to pass the time.

The more I delved into this concept, however, the more I began to consider other options. The puzzles of The Witness consist of circles and lines, but what if I simply substituted the elements? Instead of circles, what about squares? Instead of solid lines, what about striped ones or circular ones? I began to create my own patterns and view the real world through whatever lens I created.

At the risk of sounding corny, all of the sudden the world felt like a more connected place. Any object could be connected to any other object via a system you can take from a video game or create entirely on your own. The connection you find may only be perceptible to you and it might be fleeting, but there’s a way to perceive the world as a connected whole and imbue any object with meaning. All you need to do is create some rules and look in a new way.

One day, another thought occurred to me. “Could I involve other senses into this newly found puzzle perspective of mine? Are there patterns in taste or touch or sound—“ And the moment I thought “sound,” I saw the appeal of my friend’s taste in music.

Whether or not this is actually true is something you’ll have to ask him, but I began to understand that the beauty my friend finds in his music is in the construction. The way the pieces fit together, how they build, and how the parts create a whole. It's like another variation on a set of Witness puzzles. The patterns from a song make up a body. Those patterns may take on different sounds and tempos as the song goes along, but what you have in the end is a complete work. Maybe you can find similar patterns in other songs and you can link them in your mind. Maybe you can’t, but you always have the option to try so long as, again, you create some rules, and look in a new way. Or in this case, listen in a new way.

So I wandered through existence, bright eyed and bushy tailed, trying to figure out the links in the perceivable world that connected all things.

Then one day I fucked up.

Roughly around this point in The Witness, I walked into the swamp area of the map.

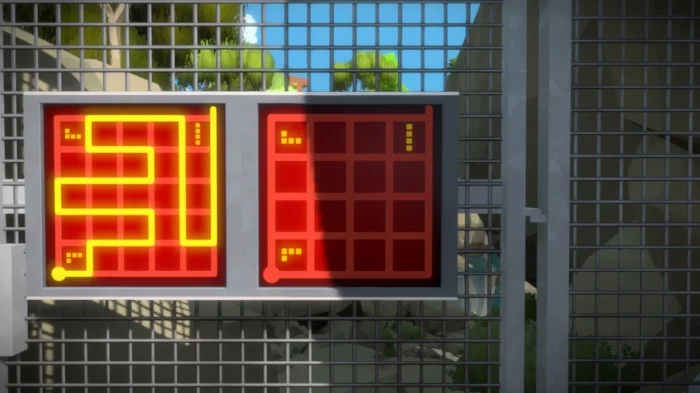

The central gimmick of the area seemed easy enough. Each panel has a Tetris piece, and you have to incorporate that shape into the puzzle solution. The tutorial puzzles work as such. (Note: I’m calling it a Tetris piece. The game doesn’t call them anything. Do not sue Jonathan Blow.):

However, something gave me pause. In the second part of the tutorial puzzles, I encountered something I’m pretty sure I hadn’t encountered before: A puzzle with multiple solutions.

That might seem liberating for some, but it was a red flag for me because now it was in my power to overthink the puzzles and lead myself down more wrong paths. Still, I went further in, and solved some more puzzles.

This is the one that broke me, in a sense.

Up until this point, I hadn’t used the internet. There were some sections that gave me a really hard time and there were some where I finally said, “Fuck it, I’ll come back to this later.” (I don't like leaving sections unfinished.) But I had never looked up a solution online. I stared at this puzzle for hours. Finally, with great shame, I looked up the answer. Turns out, the concept is simple: Just like actual Tetris blocks, the pieces can be moved around the board. The only thing you have to make sure of is that all the pieces fit together. I felt like an idiot for not having thought of it.

I continued further into the section, and I almost immediately ran into new shapes on the puzzle boards that didn’t resemble classic Tetris pieces.

Again, I couldn’t wrap my head around it, so I looked online. Turns out these non-Tetris Tetris pieces can not only be combined and moved, but also rotated.

Maybe the hours upon hours I spent playing The Witness were beginning to dull my brain. (Specifically that nightmare puzzle.) Maybe I screwed up somewhere in the tutorial section, but for whatever reason, my brain simply couldn’t process the Tetris pieces. I have no idea why, and as I continued through the swamp, I relied more and more on the internet.

Not only did the swamp break my no internet rule, but it also broke the mental inertia I had been building in my head. As I said, every puzzle concept in The Witness builds on the next. Each section of the map I encountered after the swamp utilized the Tetris pieces, and since I hadn’t developed the mental muscles to handle them, I began to rely on the internet more and more until it felt like I had to use it for almost every puzzle.

The worst consequence of all this, however, is that the new perspective I’ve been playing with in my mind all of the sudden felt completely overwhelming. No longer did I want to link objects and perceive, as Dirk Gently put it, the fundamental interconnectedness of all things. I wanted disorder. I wanted chaos. I wanted randomness and stupidity.

So I started watching more and more dumb action movies and listening to dumb music and playing all the dumb shooter games and reveling in all things system-free and dumb. You may be thinking to yourself, “But Garth, video games are, by design, a set of systems and mechanics and the movies you love utilize story structure and even if some music seems disorderly, there’s actually a set of—“ and it’s at this point that I would’ve made a fart noise or a rude hand gesture or something. The point is I didn’t have to think about the binding methodology or the order or systems. I had come full circle. I just wanted to feel.

I did finish The Witness. I saw the ending(s), but I never completed "the challenge." (To my non-gaming readers, don't ask.) I closed the game and did everything in my power not to think about it anymore. Don’t get me wrong, it’s still easily one of my favorite games of the year and I wouldn’t be writing this article if I didn’t love it dearly. I just didn’t want to be in that mind state anymore. The one where I’m constantly trying to master a pattern, even if there isn’t one.

While playing The Witness, I found myself pondering the age old debate of, “What is art?” The battle between lovers of Botticelli and lovers of Duchamp and Shakespeare and Burroughs and Beethoven and Chief Keef in the never ending war between Apollo and Dionysus.

One of the many lessons I think The Witness has to teach is that it’s silly that it’s a debate at all. We can roam around processing the abstract beauty of nature and existence, or we can look for patterns and try to find order. Both are valid perspectives, and any piece of art can be meaningful to anyone for any reason. A healthy dose of disagreement is necessary, but we enter the realm of stupidity when we say, “That isn’t art because it doesn’t live up to some random standard I've created in my head.”

For a while I enjoyed my chaotic art and didn’t go back to The Witness. Then I started writing this article, and I had to go back into the game to get the screenshots. I’ve been really enjoying it and I might play through all of it again. Hell, I might even take a whack at that challenge.

I had my friend send me a list of songs he liked so I could embed them in the beginning of the article to give you an example of his tastes. He sent me seventeen tracks. I listened to them all. They're the kinds of songs he always played for me. I had even heard one or two of them before. But you know what? I like them.