Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse

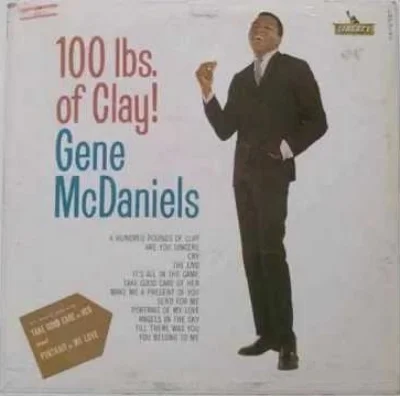

Eugene McDaniels was a singer and a songwriter whose career took off in the early ‘60s. He released music under the name Gene McDaniels, and though he had a vocal style that was a little unorthodox, he was a fairly traditional jazz and R&B singer. His work was safe and never really challenged anyone, and he had a few successful songs, including “A Hundred Pounds of Clay” and “Tower of Strength.” However, the poppy R&B music McDaniels made was beginning to lose its status in favor of more complex soul music, and Gene never had another hit.

Racial tensions in America rose to a boiling point, and after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., McDaniels left the country. When he returned a few years later, he signed to Atlantic and started recording by his birth name, Eugene McDaniels. He would release two albums under Atlantic, and let’s just say that nobody could ever accuse them of playing it safe. Here’s a picture of the cover of one of his early albums:

And here’s the cover for Outlaw, the first of his Atlantic albums:

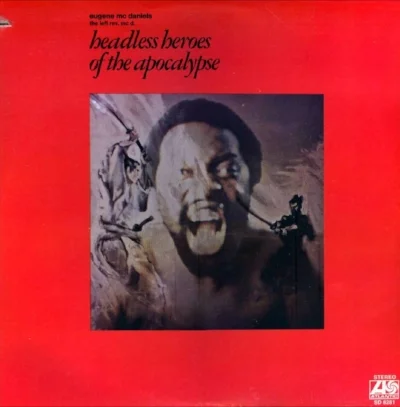

They say don’t judge a book by its cover, but Outlaw is pretty much what you think it is. It’s a vitriolic protest album infusing soul music, psychedelic rock, and jazz. Not only did this album start a new phase of his career, but it also ushered in a famous urban legend about McDaniels that partially contributed to his modern day cult status. The story goes something like this: Due to the album cover and lyrical content of Outlaw, the CIA placed McDaniels on a watchlist. Nothing really came out of this until 1971, when McDaniels released his second album, Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse.

Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse is McDaniels’s masterpiece. It also ups the anger and political discord tenfold. The album was so radical at the time that it caught the attention of then vice president Spiro Agnew, who even went so far as to have a full transcript brought into the oval office. Not long after that, Agnew called then head of Atlantic, Ahmet Ertegun, and pressured him into withdrawing the album. Ertegun complied, the album became virtually unattainable, and McDaniels’s solo career never recovered.

It’s up to you to decide how much of this story is true. (I don’t believe a lot of the details, but I absolutely believe that Ertegun was pressured.) Though his career as a singer suffered, he made a pretty decent living as a songwriter, writing such major hits as “Compared to What” and “Feel Like Makin’ Love.” (The Roberta Flack song, of course. Not the Bad Company one.) From there, he chose a life of solitude, taking an odd gig here and there. Weirdly enough, one of those gigs was voicing the character Nasus in the popular video game League of Legends. He even started a Youtube channel in his final years where he talked about his music and even uploaded some performances. In the end, he died peacefully in his sleep at his home in Maine in 2011.

Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse is an unrelentingly angry album, and I love it. Every track exudes pure pessimism and rage to a degree where most people in this day and age would find it assaultive and off-putting. This is a work from a man who’s lost faith in everything America stands for, and I don’t find it surprising that he eventually chose obscurity.

It’s also not very long, so let’s take a look at it! Though we’ll be bringing up instrumentation every once and a while, we’re mostly going to focus on lyrical content. Though the music itself is funky as hell and makes the album worth listening to in its own right, McDaniels’s lyrics are hauntingly relevant, and they speak volumes about not only the times when they were written, but the times we live in now.

1. The Lord is Back

1971 is a hell of a year to put out a song like “The Lord is Back.” It was the year COINTELPRO was exposed to the masses after a group of activists broke into an FBI office, the Black Revolutionary Assault Team bombed the South African consular office, and the Attica Prison riots received national attention. It was a time where we had definitive proof of government abusing their power. Violent intrusion into these groups were met with a violent response, and a larger confrontation seemed to be looming on the horizon.

So pretend it’s 1971. You want to release an angry soul album that will jolt people into action and scare a worm like Spiro Agnew totally shitless. You want people to hear your music and take action, or at the very least, pay attention. How would you start your album? How about a rock song about a vengeful black god coming to destroy the universe in a biblical show of angelic rage!

Bible imagery is strong in all of McDaniels’s protest works, but the god McDaniels sings about in “The Lord is Back” isn’t the merciful god that those with a religious bent turn to in their hour of need. McDaniels is referring to the vengeful god that flooded the Earth and commanded Moses to kill those who committed to the Baal of Peor. The one that will lead an army during the end times. Apocalyptic imagery is present in almost every line. “The lord is back/The lord is on the train/And he’s riding the rails to resurrection/The lord is black/His mood is in the rain/The people call he’s comin’ to make corrections.” Revelation is even specifically brought up a little later into the song. “Revelation tells us that/The time is near yeah, yeah, yeah.”

The Book of Revelation is an apocalyptic vision by John, and ultimately, this is a song about the impending confrontation between white and black people in America. Black America is on the side of the righteous, the side that will defeat the armies of hell. White America is on the side of the wicked. They aren’t led into the battle by god, but by death and destruction. Behold, a pale horse.

Despite the unrelenting rage and the assertion of violent end times, “The Lord is Back” actually manages to end on somewhat of a positive note, though it’s easy to miss if you’re not paying attention. The final lines go, “His smile is warm and soothing/As the morning light yeah, yeah, yeah.” True, it may be an abrupt change in tone, but it does remind you that this seemingly violent attitude and way of living is a reaction to the hostile society black people in America have been forced to live in their entire lives. Slavery led to Jim Crow, which led to the rise of mass incarceration and the militarization of the police. After centuries of oppression, violent confrontation is inevitable, and even foreseeable.

Yet the black soul is naturally beautiful. McDaniels casts black people in the role of the righteous not just for the fury, but also the ability to create life and culture. The love that shines through black people, like the “morning light” that shines through darkness, is a force of creation. Institutions and social codes created by white people were set for wicked reasons and ultimately keep not only black people in metaphorical darkness, but everyone else as well. It doesn’t have to be this way.

2. Jagger The Dagger

Those of you who are a little more hip hop savvy might recognize this tune. Most of the songs on Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse have been looped in one form or another, but “Jagger The Dagger” is the song that’s probably been sampled the most. You may have heard it all over A Tribe Called Quest’s Peoples Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm as the outro beat for a number of songs, including “Bonita Applebum,” “After Hours,” “Push It Along,” and a few more. You may have also heard the sample in “Nowhere to Run, Nowhere to Hide” by the Gravediggaz, “Black Sunday” by Organized Konfusion, and a few others.

“Jagger The Dagger” has continued relevance in the hip hop world not just because of the sampling, but as an early example of a “diss track.” Artists making negative songs about each other is nothing new, but at least in popular American music, it wasn’t until the ‘60s that they started getting more direct. “You Keep Her” by Joe Tex, for example, is about James Brown. He does mention “James,” but if you don’t know the context of the song, that James Brown slept with Joe’s wife and eventually married her and after they divorced sent Joe a letter telling him he could have her back, James could be anyone.

“Jagger The Dagger,” as you might’ve guessed, is directly about Mick Jagger. While he never actually says his full name, there are only so many Jaggers out there and the third line goes, “Jagger wheelin’ the rolling stone.” He’s not being particularly subtle, is my point.

Despite the bluntness of its subject matter, based purely on the lyrics, “Jagger The Dagger” is surprisingly unclear about what exactly Jagger actually did to earn McDaniels’s ire. He says he's wicked and evil, but he doesn’t really provide us with any concrete examples. It’s mostly a lot of talk about Jagger’s connection to the devil, his popularity, and his androgynous stage presence. (We’ll be coming back to that in a minute.) If you want to stretch a little, you could argue that some of the lyrics refer to Altamont, what with Jagger being a “dagger,” like the one that killed Meredith Hunter, and repeated references to knives and blamelessness. You could also say that there are references to the Rock and Roll Circus or that his ire might be drawn from a Christian uproar, but I’m reluctant to believe either of those because McDaniels usually isn’t this coy. At least not on this record.

(It’s also entirely possible that there are some references in the lyrics I’m not privy too.)

I did some digging, and the only real explanation I could find as to why McDaniels seemed to take Jagger so seriously came from Nardwuar’s 2008 interview with Questlove, an expert in soul music if there ever was one:

According to Questlove, McDaniels felt that Jagger and the Rolling Stones were appropriating the styles of black music to make a profit. The Stones were taking blues music and blues culture and using it in a manor he found undignified and racist. Whether or not you agree with that interpretation is on you. (I personally think he’s being a tad reductive, but I understand his point.) However, no matter what Jagger did or McDaniels thinks Jagger did, Jagger is one of the wicked that will be vanquished in the theoretical confrontation alluded to in the previous track. The final lines go, “Jagger’s organ will play the tune/He will watch the heavens open soon.”

There’s plenty more to talk about with “Jagger The Dagger.” The incredible instrumentation and McDaniels and backing singer Carla Cargill’s bizarre vocals come to mind. However, I think we have to talk about a certain elephant in the room. “Jagger The Dagger” comes from a certain era where traditional gender roles in American society weren’t questioned as much as they were today. As such, it’s a time where McDaniels included the lyrics, “Jagger merging the sexes now/Just stand back and he’ll show you how.” Unfortunately, he’s not talking about breaking down the barriers of gender, but reinforcing the archaic attitude that’s already there.

Though the groove is funky and it makes a great sample, I don’t listen to this song very often. I honestly can’t tell if these lines come from a place of religious anger or a skewed perception of gender, but if you’re about peace and social change, it must be about bringing us forward. Songs that include lines like this are instantly rendered false. They don’t communicate a hope of unification. Rather, they unintentionally communicate the message, “I’m not against oppression. I’m just against oppression that’s aimed at me.” These lyrics make McDaniels sound stupid and ignorant, and it ultimately ruins the song.

I’ve heard much worse in similar songs of the era, so I can get passed these lines. It’s perfectly understandable if you can’t.

3. Lovin’ Man

At face value, “Lovin’ Man” sounds like a break from the unrelenting negativity of Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse. It is, after all, about a black man who spreads a message of both emotional and physical love. One could almost argue that the song might be about Christ himself, if it weren’t for the fact that he’s a “heavy humper” that “Brings peace to virgins and spinsters.”

However, there’s a trick in McDaniels’s work that he likes to deploy every now and then, and that’s to present you with a false sense of happiness and then tear it down when you take a closer look at the lyrics. “Lovin’ Man” gives itself away in a handful of lines, but two stand out the most. The first comes around halfway through the song. So far, McDaniels hasn’t revealed anything otherworldly about our titular lovin’ man, until he says, “He has lived forever/Says that’s near not far.”

Much like John the Revelator, the lovin’ man has seen the end of the world. As it’s been hinted in the first two songs, it’s coming soon. Yet the lovin’ man continues to do that which he was put on this Earth to do, and that’s love. Of course, the lovin’ man is a metaphor. As the lyrics point out, some people are incapable of finding him and those who reject his message respond with fear. Given the Christian imagery of the last few songs, again, it’s not hard to mistake the lovin’ man for god, or at least some sort of acceptance of tolerance and holy spirit. Unfortunately, even the embodiment of love sees the apocalypse coming, and despite his presence, this all may be futile.

The other line that gives the true nature of the song away comes at the very end. The lovin’ man’s been preaching his message and having tons of righteous sex, but at the very end, McDaniels reminds you of where the lovin’ man resides. “Good thing the pigs can’t seem him/Or he’d be stopped before he could start.” The lovin’ man is an agent of harmony and peace. The police are agents of violence and prejudice. The pigs are also backed by a system greater than one man, so when the two shall meet, the lovin’ man isn’t going to wind up on top.

Whether McDaniels means “see” in a literal sense or in the sense of a spiritual awakening, again, he refers to a foreseeable end time. The lovin’ man will die in a confrontation, but it’s unclear if he’ll perish in the literal/allegorical war in Revelation or the conflict between the races in America. Given the presence of “pigs” in the last verse, I think it’s safe to assume the latter. Either way, the lovin’ man’s death is an inevitability, and it will be at the hands of a force of evil.

4. Headless Heroes

Each track on Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse runs on one of two gears: cynical or hyper-cynical. There is no middle ground. Given the content of the previous tracks, you probably figured that out by now. Believe it or not, I think we’ve only been running on regular cynical up until this song. “Headless Heroes” is when the album goes full blown existential.

“Headless Heroes” consists of four verses and a chorus. Verse one, two, and four mention a specific conflict that’s been brewing between certain groups of people for hundreds of years. Verse one is about Jews and Arabs. “Jews and the Arabs/Semitic pawns in the master game/The player who controls the board sees them all as the same/Basically, cannon fodder.” Verse two addresses the conflict between the left and right wing, and verse four focuses on “niggas and crackers.” Other than the change to “political pawns” and “racial pawns” respectively, these verses follow the same structure and lyrics. Both sides of each conflict don’t matter to those who control the world, and neither do their comparatively petty conflicts.

The final verse reveals the players of the game. “Industry and war machines/They are the kings in the master game/The player and the king are one and the same/We are the cannon fodder.” These are the systems that keep these conflicts going. They’re indifferent to the needs and ideology of each group. They’re also indifferent to who you are and what you stand for because in the end, their only goal is to make money.

You can argue over who has the right to which piece of land or who did what in whichever holy book all you want. You can write aggressively political Facebook statuses until your fingers go numb. You can protest and riot until you’re all rioted out. None of it matters. The cause, the sides, you, none of it. There is a system that benefits from the state of constant conflict in the world, and whether you’re on one side of a problem or the other, you’re still benefitting a system that takes advantage of your outrage and your action to make money. You are compromised and nothing you do matters.

So what can you do about it? According to McDaniels, nothing. As the chorus says, “Still nobody knows who the enemy is/‘Cause he never goes in hiding/He’s slitting our throats right in front of our eyes/While we pull the casket he’s riding.” The enemy has no need for hiding. He/it is too powerful to care about what we think or do. There is no way out, and everything we choose to do or care about is ultimately meaningless. There is no answer.

Again. Hyper-cynicism.

5. Susan Jane

I have a theory about “Susan Jane,” the lightest song on the album. It’s not that deep or insightful a theory, but I feel like it’s worth pointing out anyway. “Susan Jane” is pretty blatantly done in the style of a Bob Dylan song. It abandons the soul and funk instrumentations in favor of a more traditional folk arrangement: One acoustic guitar, a bass, and some drums. The lyrical structure and the way McDaniels sings the song also invoke Dylan in pretty unsubtle ways. Except for the break in each verse, “Barefoot in the muddy road,” he keeps the rhyme going for six lines rather than two, as well as adding a Dylan-esque inflection onto certain words. “Cane” and “pain,” for example, become exaggerated “cAYEne” and “pAYEne.” (Listen to it and it’ll make more sense.)

It’s also Dylan-like in subject matter. While not as wordy or lengthy as a Dylan song, it follows the Dylan formula of, “The narrator encounters a strange person or a group of strange people who live outside of societal norms and describes the encounter.” (Yes, that’s a bit of a generalization of a certain kind of Dylan song, but you get my point.) In this case, our outsider is Susan Jane. She lives the “free love” lifestyle of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. She travels the country without shoes, she likes to party and has sex when she feels like it, and she seeks a spiritual awakening and an unencumbered state of being.

When looking up what others thought of this song, most people call it an homage or a tribute. My theory is that the song is a parody, and the reason I think that is because of the last verse. McDaniels has been describing Susan’s hippie lifestyle for the whole of the song thus far, then at the end, he reveals where Susan came from. “Used to have a maid/In the Palisades/Her father’s Christ crusade/Did not include the spades/Never made the social grade/Enjoys getting laid/Barefoot in the muddy road.”

Susan’s rich and her Christian father is a racist. Once she’s done living this way, she’s free to return to her affluent life in California and forget any of it ever happened. We’re free to wonder whether or not she ever will, but that option is always available to her, unlike the suffering black population McDaniels has been singing about in this album so far. No matter how hard Susan tries to fight it, she can never escape where she came from.

I said I think this song is parody. Dylan gets into issues of class and race all the time, and you still may see it as an homage. You’ll forgive me though if I don’t choose to believe that McDaniels is all of the sudden going to start holding back his punches.

6. Freedom Death Dance

“Freedom Death Dance” returns us back into the realm of the existential and the hyper-cynical. “Headless Heroes” informs you that your struggle and the issues that you think are important ultimately don’t matter. However, according to “Freedom Death Dance,” your happiness doesn’t matter either! Yaaaaay!

Despite the angry or depressing subject matter, most of the songs on Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse have a certain degree of energy to them. “Freedom Death Dance” starts slow, and it starts dour. “Everybody wants happiness/Everybody wants peace of mind/Everybody says we should ignore/The graves we dance upon/But I really got news for you/There’s no amount of dancing you can do/That will ban the bomb/Feed the starving children/Bring justice and equality to you and me/No amount of dancing’s gonna make us free.”

The social movements of the late ‘60s were not only about the advancement of human rights, but also about a sense of unity in oppressed communities. We had to get together and free love and all the other platitudes common in the era. McDaniels is essentially saying that unification and solidarity are empty without action. To dance and temporarily shake off the oppression that confronts you at every corner is a means to a fleeting moment of happiness, but nothing more.

He then continues, “Gather round the riots children/Everybody wants to dance/Gather round the murders and be free/Gather round the breath of life/The could be your only chance/To be in touch with your own humanity.” Protest for the sake of spiritual elevation rather than actual change is empty protest. When a human being is murdered by an agent of the government unjustly, you can’t solve the problem by dancing at it. To confront the darkness is to remind you of what makes you human.

“Free love” is a drug. It numbs you from the pain so you no longer have to confront it, let alone take the steps necessary to solve your problems. As long as we’re all dancing, as long as our protests are empty, as long as our form of social movements remain in service of the self rather than the desire to actually make change, there will always be more graves to dance upon.

7. Supermarket Blues

“Supermarket Blues” attempts something up until this point the album hasn’t tried yet: Humor. This is still a Eugene McDaniels song and we’re still listening to Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse, so obviously the humor is still incredibly dark and shrouded with anger over the state of race relations in America. But it still tries to be funny, and it actually kind of succeeds. I love the exaggerated “GODDAMN” that pops up every once in a while.

The story goes like this: Eugene goes to the supermarket to return a can of pineapples he bought because for some reason, it's turned into a can of peas. Naturally, the supermarket manager starts to beat him, and then the crowd cheers as an old lady starts to beat him, and then eventually the cops, who also threaten to kill him. He tries to invoke his constitutional rights, but the old lady calls him a “communist jerk” and a “savage” because he’s black. The only thing he can do is wish that he stayed home and gotten high.

He was sold a lie by a white run institution, he tried to do something about it, and he was met with violence. The end.

There isn’t much to say about “Supermarket Blues” that isn’t already on the surface. The violence is casual, the circumstances seem to be common, or at the very least the story is presented in such a way as to be relatively unremarkable, and the message of the song is abundantly clear.

The only thing left to say is that if you’ve watched the news or been on social media anytime in the last few years, you can see why this song may be alarmingly relevant right now. It’s sad how little has changed.

8. The Parasite (For Buffy)

“The Parasite,” the nine and a half minute closer of Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse is… fucking incredible. Half the reason I wanted to write this article in the first place was just so I could express to you how much I love this song. It’s my favorite on the album, and somehow, it also manages to achieve a level of anger and despondency Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse hasn’t reached thus far.

“The Parasite” doesn’t achieve this feat using any of the methods McDaniels has used thus far. There is no apocalyptic doom or existential ponderance or comedic hyperbole. “The Parasite” simply tells the story of the pilgrims. The chorus goes, “They landed at Plymouth/With a smile on their face/They said we’re your brothers/From a faraway place/The Indians greeted them/With wide open arms/Too simple minded and trusting/To see through the charms.”

The song tells the story of colonization. First the pilgrims, “ex-hoodlums and jailbirds,” saw a chance for a new start. They landed in their new home, took a look at their surroundings and the people who already lived there, and decided that they wouldn’t do. Slowly but surely, they set about destroying the Native American’s culture, their bodies, their home, and everything they cared about. Now we’re in the modern era, and the Native Americans are all but gone.

It’s a story that’s been told for hundreds of years, but it’s a story that never loses its power, especially when told by someone as angry as Eugene McDaniels. In “The Parasite,” McDaniels’s lyrics are unflinching and damning, but he also delivers them with an almost ancient rage. (The first time I ever listened to the song, the way he yelled, “POLLUTING THE WATER/GODDAMN/DEFILING THE AIR” sent chills down my spine.) With each verse, he sounds like he’s losing more and more control of his delivery, and, at the very end of the song, when you’re expecting the chorus one last time, the music devolves into chaos and McDaniels screams with a guttural pain. The screaming continues for the last minute and twenty seconds. And then silence.

The “Buffy” referred to in the full title of the song is Buffy Saint-Marie, a native Canadian folksinger who was blacklisted in the United States for the political nature of her songs. McDaniels, upon the release of Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse, would meet a similar fate. He still achieved success as a writer, and he even released one or two more albums that didn’t achieve the same cult status as this one, but much like Buffy, he was more or less silenced by the American government, be it directly or indirectly.

“The Parasite,” and really all of Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse, serves unintentionally as McDaniels not going quietly into that good night. A final rage against the dying of the light. Some other poetry reference. I think McDaniels saw himself as a member of a group that was slowly being driven into the ground by white America. At a certain point, the only thing he could do is look backwards and realize that all of this has happened before.

Much like John, I think he could see the end coming.

Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse was an album for then, and it’s certainly an album for now. It’ll be a cold day in hell before we see any radical groups of millennials willing to bomb an embassy or break a political prisoner out of confinement, and we’re probably better off for that. It does, however, feel like a confrontation is coming. There’s an election happening in a few weeks. As of now, it looks like Trump’s going to lose, but the times still feel dark. (EDIT 12/6/2016: Fuck me, right?) The positivity that surrounded the inauguration of Obama has been all but snuffed out, and it may be some time before we see anything like that happen ever again.

It’s in times like this that I find solace in Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse. It may seem foolish to say that you find any positivity in something this bleak, but if there’s one quality that this album abounds in, it’s integrity. Say McDaniels is a pessimist. Say his message is counterproductive and distasteful. McDaniels never lies to you, and at this moment, I find that extraordinarily comforting.